|

"The getting to know you meeting" is what I call the very first session but I use it to make sure you assess me and the therapy process. I want to make sure you 're comfortable and committed to the task. It also allows me to get a feel of your expectations for the therapy.

I also look for some basic information, including any previous diagnosis and your address and phone number. I hook you up (as an example of the procedure) to a simple surface ElectroMyoGram (sEMG) just so you can see your muscle activity increasing and decreasing as you tighten and relax your extensors (muscles in your wrist). At the end of the session I ask if it all makes sense. If so, you can either schedule an appointment at that point or give me a call. If you think you will continue, I give you an intake and evaluation form so when you arrive back for the second session, where I'll conduct the Psychophysiological Stress Profile (PSP), you can also give me the completed form. The point of it all is to start you thinking and noticing yourself. You have probably already noticed your emotions but this may kick-start a process where you become aware of your own thoughts and behaviours. The form also acts as a checklist. Each question can potentially become a talking point when you bring back the form. I encourage people to have questions for me as well. If it can be measured, it can be fed back but as biofeedback therapists

With these concepts foremost in our minds, we can measure and feedback a host of different bodily functions. At Biofeedback Ireland we routinely measure and feedback:

There are other many other modalities used by therapists who want a closer look or to get finer detail about a process. For example, a respiratory technician or someone interested might use a caponometer to look at the amount of carbon dioxide you may be exhaling when you breathe. Or for finer detail, I worked with a physiotherapist (PT) who routinely connected her patients to 16 SEMGs so she could accurately see how her patients were recruiting various muscles while she was helping them with rehabilitation after they sustained a Spinal Cord Injury (SCI). I will go into more detail describing each modality in later blogs. There’s a lot has been written about stress and anxiety over the years. “Stress” seems to be one of those words that everybody uses and we all feel we’re stressed, that we live a stressful lifestyle (and we're probably right). Here’s a game though, imagine a conversation between you and a student that doesn’t speak your language. Student: I keep hearing the word “Stress”. What does it mean? You: Oh that’s easy it’s……… (OK, now take over, keep it concise and make sure the student can understand it.) My guess is that it’s not as easy as you thought. It reminds me of that colloquial phrase that originally came from the Supreme Court in the US, “I don’t what it is but I know it when I see it”. In biofeedback, we have to be a bit more specific and we have to make sure you and the therapist are using the word in the same way. Stress is a change in a physiological system above or below homeostasis. A stressor is something that causes that change. OK, to explain it. The word “Homeostasis” is not one that most people will have encountered since secondary school. It basically means balance. So here’s how it works: You’re reasonably relaxed, watching some TV, and your heart is beating at 72 beats per minute. Suddenly you hear a bang (it’s probably just the kids but you’d better check). You climb the stairs your pulse quickens slightly as you go (you tell yourself that you really must get more exercise). By the time you’re at the top you may be working at 110 beats per minute. That’s not a problem. That’s exactly what’s supposed to happen. Your heart adjusts to the new demands but so does your blood pressure, digestion, temperature, sweat, breathing etc. You shout at the kids and go back down again. When you get back to the couch you settle back in, probably grunt or sigh as you expel air, and everything returns to homeostasis. So what you’ve done is increased your heart rate (above homeostasis) in response to a stressor (movement, the kids, guilt depending on how you look at it). But, and this is the important bit, you quietened down again soon after. You returned to homeostasis. If the stressor was something else though, like an argument or a job interview or a presentation and you don’t switch off, that’s when you start to lose sleep, get headaches, aches. Now you can safely say “I’m stressed!” If I’m seeing somebody for the first time I need to know how to get a hold of them again but I also need to know a plethora of information that the intake process in any therapy program should gather. Most importantly for biofeedback therapy though, I need to know how a you react to the various types of stressors that have a tendency to present themselves during the day. I want to see if you let the effects of the stressor diminish quickly and efficiently (most people including myself don't.)

I also want the you to know the difference between a stressor and stress. I would like to know how you react to different types of relaxation exercise as well. I want to accomplish this in the first 3 sessions if possible, but the question is how to get this information quickly and at the beginning of the therapy program. In addition to the standard assessments I conduct a Psychophysiological Stress Profile (PSP). There are many examples of different types of PSP but it should consist of a number of tasks that introduce a mild stressor and then let the person relax after the stressor has been introduced. The therapist needs to measure all of the modalities that they usually use during a therapy session. I have used the same type of PSP for many years, but recently my practice has quietened down and I am reassessing it. I've been reading “The Clinical Handbook of Biofeedback” by Inna Khazan. Her approach to biofeedback is to integrate the mindfulness component as strongly as possible. I have been doing this for many years, but in chapter 4 she addresses the initial evaluation. She has made me think about redesigning my initial assessment and I have been rereading texts that detail the various possibilities and changed things around a bit  In a biofeedback session we measure and record a whole plethora of physiological measures every time you train. As a result you can easily see changes in your physiology. That’s what the whole process of biofeedback hinges on. You have to be able to accurately see (or hear) yourself. The result of this is that you can look at every one of your sessions as an evaluation. Despite this, it’s still a good idea for you and the therapist to formalise a few of them. So let’s formalise three of them:

In our case, for the initial evaluation, we use a “Locus of Control” questionnaire, a conversation, a breathing questionnaire, a Psychophysiological Stress Profile (18 min recording using the instruments) and an intake form. It all takes about 2 hours.

The first and last evaluations are similar. The first recorded session gives us a baseline to compare against and the last evaluation should show a change. There may also be a difference in the ‘Locus of Control’ assessment. The progress evaluation is a lot more informal. Rather than just completely rely on data from the instruments it's a session designed for you to assess everything and ask loads of questions. It also falls around the time where we move from an educational format to a more proactive one. You'll start directing the approach we and be more involved because you will understand what's going on I had started to write about biofeedback evaluations (I’ll get back to it) but I received a lot of requests to talk some more about triggers and how they work on a daily basis. So here goes:

Everyone with a chronic issue has identified stressors (biological, psychological and social) that act as triggers. Previously, in a post about headaches, I wrote about how triggers were cumulative but there’s another aspect to them that deserves to be looked at. In regards to migraine I wrote“sometimes what will trigger a migraine on one day may not trigger it on another”. That seemed to cause some confusion so I'll explain. Let’s broaden out a bit beyond migraines though. The same idea holds true for anyone with a chronic pain, anxiety, CRPS, headache, depression, arthritis, cardiac conditions etc. This is how it works: You get up on a Sunday, the sun is shining, you’re going for a picnic with your family and you’re in a good mood. You have a shower, go back into the bedroom to put on clothes and stub your toe on the wardrobe. “Oh F#!@” you yell, grab your toe and check your nail. You move on quickly though “Where did I put the corkscrew and I suppose we’ll need a blanket……… Alternatively, you get up on Monday, it’s grey and raining. A full week of work ahead and you’ve got to spend the first part of the morning with your boss in a meeting. Mood - not so great. You have a shower, go back into the bedroom and stub your toe on the wardrobe again. “Oh F#!@” you yell, grab your toe, check your nail, just like you did yesterday but you don’t move on this time. Instead you begin talking to yourself “jeez that was stupid, what a way to start my week” or “I can’t believe I did that, that bloody hurts, I probably won’t be able to walk properly for the rest of the day”. It’s all a bit harsh and you’d never say that stuff to a friend (you might slag them off a bit but you’d be sympathetic, I hope). You’re quite happy saying it to yourself though. What’s important to realise is that not only does the pain feel seem to feel worse on Monday; it is, you’ve actually changed the way your body processes the sensation. The chemicals and the pathways that you use to transmit the pain signals have been altered because your mood is different, not to mention the negativity around telling yourself that you’re “stupid”. So in addition to the triggers being cumulative (see the last post) you have a situation where the same trigger at two different times can have a completely different impact because of the mood you’re in. We’ve only talked about a situation where you can easily see the trigger i.e. in this case it’s immediately painful but the same holds true for any trigger whether you are conscious of it or not. Let’s take a food additive that has routinely caused trouble before: You’re out to dinner with your nearest and dearest and the chef has put ‘that’ additive in your dish but it doesn’t trigger anything (you’re relaxed and the future looks good). Now the following evening you’re at home cooking after a tough day at work. You accidently include ‘that’ additive but because you’re tired and cranky this time, it acts as a trigger. The sum of it and all the other potential triggers you have encountered that day and …ouch! Or here’s another: You’ve got to give a presentation at work that afternoon. Normally that’s enough to cause you to have a panic attack/anxiety episode (you don’t like public speaking) but you are going out with friends later that evening. Because you are looking forward to going out, you’re feeling a bit more upbeat than usual and the anxiety doesn’t trigger the panic (this time). You get the idea, it’s not just the stressor it’s how you perceive the stressor or in this case, the mood you’re in when you perceive the trigger.  When we start biofeedback training we usually begin with breathing. It’s often used as an anchor for many other techniques taught by biofeedback therapists/clinical psychophysiologists. There are 2 big matters that we need to look at first.

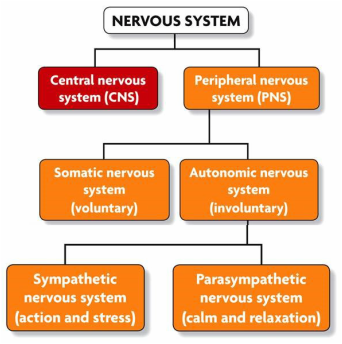

To answer the first question: Why breathing? For one really good answer we have to look at a simple diagram of the nervous system. This diagram and others like it are in high school/secondary and basic anatomy and physiology texts all over the world. They help you understand how you’re wired. (The actual length of the wiring or nervous system depends on how you count but I’ve seen figures that range from 45 to 90,000 miles, one way or another it’s huge, try laying 45 miles of electrical wire sometime, never mind 90,000)

OK, simple question:

To answer the second question: I’ve learned how to breath already, do I have to do it again?

To see the immediate physiological effects you can look at Carbon Dioxide and how much is in your breath or you can look at your Heart Rate and how much it varies. I’ll cover these modalities in a later post. A lot of people think their heart beats at the same rate all the time….but it doesn’t. We get the impression that it’s unchanging because when we take our pulse we normally take it for a minute and average it, but it’s not that simple.

We had spoken in an earlier blog that even the simple act of moving changes pretty much everything in your body including your HR “So here’s how it works: You’re reasonably relaxed, watching some TV, and your heart is beating at 72 beats per minute. Suddenly you hear a bang (it’s probably just the kids but you’d better check). You climb the stairs your pulse quickens slightly as you go (you tell yourself that you really must get more exercise). By the time you’re at the top you may be working at 110 beats per minute. That’s not a problem. That’s exactly what’s supposed to happen. Your heart adjusts to the new demands but so does your blood pressure, digestion, temperature, sweat, breathing etc. You shout at the kids and go back down again. When you get back to the couch you settle back in, probably grunt or sigh as you expel air” and you return everything to an unstressed balance (homeostasis/allostasis). This is the scenario we are all familiar with and any stressor (internal, perceived or external) will result in us adjusting something to deal with it more efficiently. So with heart rate we can easily see that it:

But here’s the kicker, they are all causing the heart rate to increase and decrease at different times. It’s like listening to an orchestra where all the members are tuning their instruments but playing something different, a cacophony. Here comes the conductor, she says to everyone, follow my lead and play together. Our equivalent of the conductor is your breathing. If we can teach you to breath at your pace (between 4.5 and 7 breaths per minute), you become the conductor and everything starts to play together. Your heart rate starts to swing dramatically at a regular rate. In the next installment I’ll explain a bit more Heads up right from the beginning:

If you suspect that you experience migraines, organise to have them/you checked out by your physician. In Ireland, if you wish to have an in-depth assessment, set up an appointment with one of the headache clinics in the country. The Migraine Association of Ireland has contact information: http://www.migraine.ie The first thing to realise is that a Migraine headache is not a just a headache, it’s a neurological disorder with headache as a symptom. Sometimes (it’s rare) but people don’t even get headaches, they get might experience nausea or even get an aura without any pain. There’s a term: “Biopsychosocial”. It comes up when managing all sorts of chronic issues (remember chronic doesn’t mean bad, it means long-term or repeating). The term implies that chronic issues have biological, psychological and social components. You can use this concept to help identify triggers as well. A trigger is anything that contributes to the onset of a migraine. As I said before, a trigger can be biological, psychological or social. Indeed, triggers are always a combination of all 3 (whether you can see it at the time or not). The important thing to realise is that triggers are also cumulative and sometimes what will trigger a migraine on one day may not trigger it on another. In another post I’ll talk about how potential triggers change on a daily basis. In regard to their cumulative nature let me give you an example: Imagine that you will get a migraine when you reach 10 points (a purely fictional number). You won’t get to the 10 the same way every time but when you do you’ll get a migraine.

You've totaled 16 points so the migraine is inevitable and on the way (if not already here) Instead you learn to manage everything a bit more efficiently (It takes weeks but you do it): You learn how sleep a bit better so instead of it being 4 it's now a 1. You’re a little less anxious about that meeting/presentation so instead of it being a 2 it's now a 1. You have started to exercise regularly so instead of it being a 3 it's now at 0. You’ve become convinced that the food you ate was not as big a trigger as you thought so instead of it being a 2 it's 1.5. You’ve re-assessed the argument and your mood is slightly better. Instead of it being a 2 your still upset but not as much so it's down to 1.5. The medication you’re taking is suitable and helps you head off the headache and because you've got better advice and acted on it the meds aren't contributing so they go from a 3 to 0. Total 5 You’re only at 5 points so the migraine is not going to happen This is how management using the biopsychosocial model works. Biofeedback in general and Biofeedback Ireland specialises in helping you identify and knit all the different aspects of the biopsychosocial model. If we look at the six components we already listed you can see how this works.

Sometimes the misuse of the medication can be a cause of the headache being worse such as with a medication overuse headache. Getting the balance right is essential. Most biofeedback therapists/psychophysiologists are psychologists and do not prescribe. Work with your general physician or specialist to get your meds working for you. |

Daren Drysdale

I'm a Dad with a PhD, a psychologist, a clinical psychophysiologist and biofeedback therapist ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed